The current year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to two scientists who changed a dark bacterial immune mechanism, generally called CRISPR, into an apparatus that can just and efficiently alter the genomes of everything from wheat to mosquitoes to people.

The award went mutually to Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens and Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, “for the advancement of a strategy for genome altering.” They previously indicated that CRISPR—which represents bunched normally interspaced short palindromic repeats—could alter DNA in an in vitro system in a paper distributed in the 28 June 2012 issue of Science. Their disclosure was quickly developed by numerous others and soon made CRISPR a typical instrument in labs around the globe. The genome editor generated enterprises taking a shot at making new medications, agricultural items, and approaches to control pests.

Numerous scientists foreseen that Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute, who demonstrated a half year later that CRISPR worked in mammalian cells, would share the prize. The establishments of the three scientists are secured a furious patent fight over who merits the protected innovation rights to CRISPR’s revelation, which some gauge could be worth billions of dollars.

CRISPR was likewise utilized in one of the most disputable biomedical experiment of the previous decade, when a Chinese scientist altered the genomes of human incipient organisms, bringing about the introduction of three children with adjusted genes. He was broadly sentenced and in the long run condemned to prison in China, a country that has become a pioneer leader in different regions of CRISPR research.

Although scientists were not surprised Doudna and Charpentier won the prize, Charpentier was stunned. At a press briefing today, Doudna noted she was sleeping and missed the underlying calls from Sweden, possibly awakening to pick up the telephone at long last when a Nature journalist called. No previous science Nobel has been given to two women only. Doudna added that she used to get confused looks when she said she worked away at a bacterial invulnerable system. Bacteria utilize the first type of CRISPR to battle off infections, cutting up their DNA.

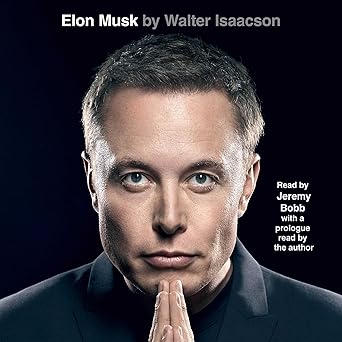

Discover the mind behind the innovations – Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson, now on Audible. Dive into the life of a visionary shaping our future!

View on Amazon

“The ability to cut DNA where you want has revolutionized the life sciences.”

Pernilla Wittung Stafshede, Chalmers University of Technology

Doudna and Charpentier—who is initially from France and at the time of the disclosure worked at Umeå University—demonstrated they could program a little portion of what they called “guide RNA” to convey a bacterial CRISPR-related (Cas) compound to correct DNA groupings, permitting them to target explicit genes. Cas at that point cuts the twofold abandoned DNA. In many cases, the DNA fix mechanism of the cell makes mistakes, which can injure a gene—taking out a gene in this style is a powerful method to contemplate its ordinary job. CRISPR additionally permits scientists to embed another stretch of DNA at the cut site.